Week 20: Attending an Academic Conference is #BetterByBicycle

One of the things I love about being a teacher is that I am exposed to so many learning opportunities. I just have to pick the ones that are aligned with my interests and values. So last week I got fortunate to get a slot to the International Conference on Environmental Humanities in the Philippines and Southeast Asia. Jointly organized by the Department of History at UP Diliman (UPD), the Department of History at Ateneo de Manila University (ADMU), and the Department of History at the National University of Singapore (NUS), the conference served as a platform to bridge the humanities and sciences in exploring pressing issues related to the evolving natural environment in the Philippines and Southeast Asia. It showcased 24 paper presentations designed to encourage dialogue on various environmental concerns.

Now I'd like to share a little bit about what I've learned from the conference. First of all, I want to say this conference is a first of its kind, at least here in the Philippines so I was really excited when I learned about it and immediately signed up. For so long, I have felt that there has been a silent divide between physical and social sciences in the Philippine academic landscape. For one thing, there is a systemic bias favoring STEM fields over the social sciences as manifested through funding disparity, institutional support, and public perception. Then there's the epistemic divide - hard sciences value quantifiable, measurable and empirical data, while social sciences focus on complexity, context, and lived experiences. And I'm not saying that one has to take a pick in understanding real world problems and solutions. There is an urgent need for transdisciplinary work, a collaboration among disciplines. Over-reliance on technical fixes without understanding human behavior, culture, or governance will often lead to failed projects or even unintended harm. Social sciences are key to surfacing indigenous knowledge and practices, community values, and historical context—crucial for sustainable and inclusive development. This scholarly division, inherited from colonial legacies is an intellectual inconvenience and a barrier to real-world change. As Prof. Emma Porio (one of the presenters) puts it, we need to decolonize scholarship by naturalizing social sciences, and humanizing natural sciences. We currently face our greatest existential crises -climate change, human health decay, social unrest, etc., and the need for collaboration between hard and soft sciences is essential, this conference addresses this glaring academic segregation in our region.

On Hazards and Climates

Prof. Diego Rabato talked about the effects of hazards on Novo Ecijanos from 1880s to 1910s as a result of land use conversions, forests were cleared to make way for monocropping, an efficient way to feed a colony focused on cash crops. Today, Nueva Ecija is known as the "Rice Granary of the Philippines". And the price? Heightened exposure to hazards like flooding and dry spells. My father is from Nueva Ecija, so I know that it is one of the hottest areas during summer while it is the second most flood prone province according to DENR. A lot of Filipinos attribute deforestation to logging and mining, while it's true, we should also keep in mind that a huge part of land use is allocated to agriculture.

For me, what stands out is not just the physical transformation, but the psychological and social ripple effects that followed. Imagine watching your local environment disappear. Imagine enduring more frequent floods and longer droughts because the trees that once regulated the climate and water flow are gone. Then imagine being pushed off that very land due to new systems of ownership that favor large landholders. That’s not just environmental degradation; that’s a recipe for chronic stress, insecurity, and ultimately, unrest.

What strikes me most is the human cost behind the data. It’s not just about emissions or economic models, it’s about how people feel, adapt, and suffer through the invisible pressures of environmental inequality. From a psychological perspective, these conditions will cause profound psychological strain. The mental toll of losing your home to floods, living in heat islands without green space, or being left out of disaster recovery efforts isn’t often talked about, but it’s real. Climate solutions must consider the emotional and social landscapes we inhabit, not just the physical ones. Cities aren't just concrete jungles, they are psychological ecosystems. If we want justice, we have to start designing AND feeling for everyone.

On Plants and Global Mobility

Professor Timothy Barnard discussed the introduction and spread of the water hyacinth in Southeast Asia, originally brought from South America to colonial botanical gardens for its aesthetic appeal and practical uses such as a counter for algae blooms, provide animal feed and act as compost, or biochar. Despite intentions to beautify landscapes and provide ecological benefits, the plant rapidly proliferated, disrupting native ecosystems and reducing biodiversity by outcompeting local flora and depleting oxygen levels. I find stories like this fascinating and sobering. On the surface, it’s just a plant - beautiful, floating, seemingly harmless. But underneath lies a deeper story about how well-meaning intentions, shaped by colonial ideals and aesthetic values, can spiral into long-term ecological disruption.

This was a classic case of environmental misjudgment, where human perception of beauty and utility overrides ecological understanding. It speaks volumes about how our cognitive biases and cultural frameworks shape environmental decisions. Such decision was based on a short-term perception rather than long-term ecological insight. The effects of of ecological damage continue to shape how people interact with and emotionally respond to their environments today, especially in communities that rely on these waters for livelihood and sustenance.

This story also reminds us that our relationship with the environment is shaped not just by policy or science, but by culture, emotion, and identity. Plants like the water hyacinth aren’t just ecological actors; they are also symbols of how power, aesthetics, and psychology have intertwined in shaping environmental legacies. In the face of climate and biodiversity crises, we need more than ecological science, we also need psychological insight to challenge our assumptions and make more mindful, future-proof choices.

On Ecological Changes and Local Responses

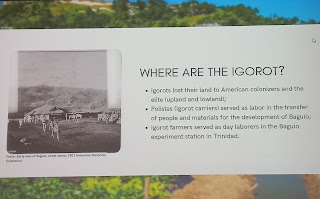

Prof. Marie Beatriz Gulinao talked about how Baguio was transformed to suit the needs of the American colonial government in the guise of its civilizing mission in the Philippines. Her research revealed how Baguio's development wasn’t just about roads, buildings, or agriculture, but also about crafting a specific kind of space to serve a specific kind of colonial vision. The Americans saw Baguio, with its climate, a place that mimicked the temperate zones they were familiar with. The urbanization of Baguio represents more than material change, it reflects a deliberate effort to impose a new identity onto the land. The city was crafted as a summer capital, a controlled environment where American officials could retreat and feel “at home.” The agricultural experiment stations showed attempts to grow imported vegetables, which mirrored broader efforts to transplant Western values and systems into local soil.

From a psychological lens, this kind of improvisation reveals a deeper relationship between people and place. Homes became hybrid spaces, not just sites of domesticity, but of labor, food production, and ecological negotiation. Living alongside animals in dense urban areas also brings with it psychological shifts -new routines, sensory experiences, and altered perceptions of what a home should be. It challenges the Western ideal of clean, compartmentalized urban living and instead offers a model of flexibility born out of necessity.

The presence of pigs in cities may seem peculiar, even cute to some, but for those living through that period, it embodied a remarkable story of psychological and environmental resilience. In a time of material scarcity, people remade their environments—and in doing so, remade themselves. Sometimes, resilience doesn't look like strength. Sometimes, it looks like a pig in the living room. And speaking of pig and Viet Nam, I suddenly remember a time when I came across a piglet in the streets of Hoi An in one of my cycling trips while I was there 😁

On Marginalized Spaces and Environmental Voices

The last paper that I want to share is Prof. Remmon Barbaza's Lakad, lapit (Walking, nearness): Reviving the habit of walking and rediscovering nearness on the way to ecological justice. His presentation explored how reviving the Filipino practice of walking and rediscovering nearness -inspired by Heidegger’s phenomenology are deeply connected aspects of being human. He points out how the word lakad is embedded in the Filipino culture, not just as an act of walking but a multitude of meaningful activities, such us going out with friends, or running an errand, or processing some papers, etc. I love how he emphasized that we think of our space in terms of nearness to a particular landmark or place rather than in terms of longitude and latitude coordinates. He pointed out that these embodied practices are not only vital for personal and communal reconnection but also essential for healing socio-political divides and advancing ecological justice in the Philippines.

From a psychological standpoint, walking has long been recognized for its therapeutic effects - reducing stress, enhancing mood, and fostering cognitive clarity. But when paired with nearness, it becomes more than therapy. It becomes a form of ecological and social reconnection. In today's modern life, the traffic, gadget screens, and social fragmentation often distances us from one another and from the natural world. Walking (and cycling!) is a quiet form of resistance, an act of reclaiming agency, re-rooting ourselves in shared spaces, and bridging the social, political, and environmental divide that continue to widen.

I really enjoyed attending this conference. My resolve to follow the path of environmental psychology was reinforced. Cause when I think about it, across forests, cities, fields, and alleyways, a common thread emerges: the environment is never just a backdrop to humanity, it is intimately tied to identity, memory, power, and psychological well-being. These stories -from colonial Nueva Ecija to post-war Hanoi, from the invasive spread of water hyacinths to the symbolic weight of pigs in urban homes, reveal that environmental change is not only ecological or economic, but deeply emotional and psychological. Throughout these reflections, one insight stands out: our environments shape us as much as we shape them. If we are to address today’s environmental crises meaningfully, we must look beyond science and policy and listen to the emotional landscapes people inhabit. We must also consider psychological insight, cultural context, and historical memory in our understanding of sustainability and justice. Because ultimately, to care for the Earth is also to care for the minds and hearts shaped by it.

Comments

Post a Comment